- Store

- >

- Literature & Art

- >

- 1889 Paul Gauguin autograph manuscript "On Huysmans and Redon"

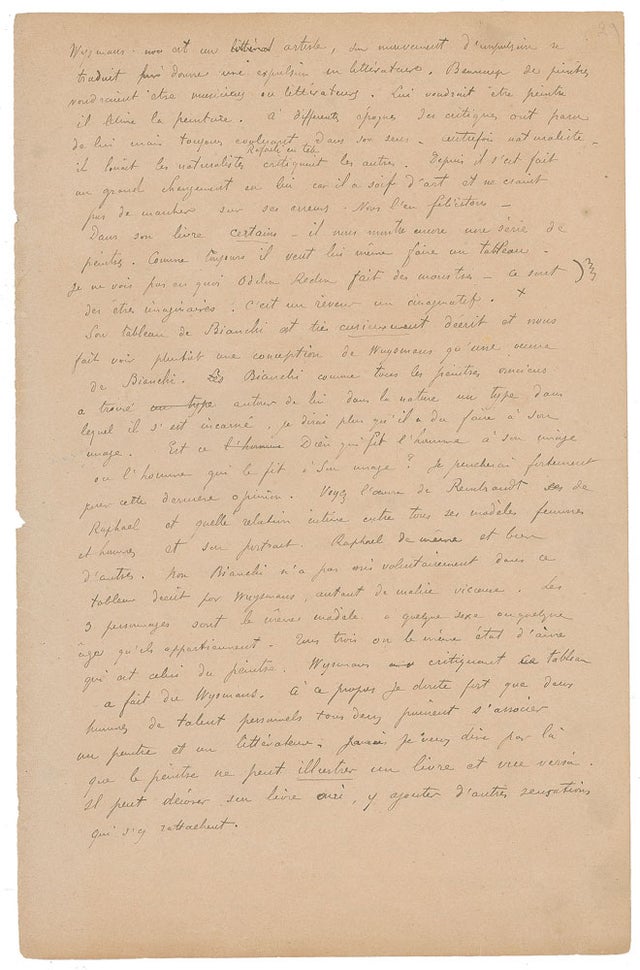

1889 Paul Gauguin autograph manuscript "On Huysmans and Redon"

SKU:

£14,500.00

£14,500.00

Unavailable

per item

Scarce autograph manuscript by Paul Gauguin; a working draft of an article "On Huysmans and Redon", circa 1889. In French. 3 1⁄4 pages, 12.25 x 8". Sold with a copy of Gauguin, Oviri: Ecrits d'un sauvage. Gauguin muses on contemporary art, highlighted by a lengthy discussion of Odilon Redon and the novelist and art critic, Joris-Karl Huysmans. He also touches on many other art world names, including Gustave Moreau, Puvis de Chavanne, Francesco Bianchi, Rembrandt and Raphael.

The final article was published in the book "Gauguin, Oviri: Ecrits d'un sauvage", edited by Daniel Guérin (1974), pp. 59-61, dating it 'fin 1889', and noting that it was first published in Les Nouvelles littéraires, 7 May 1953. The manuscript shows significant differences from the published text, with a number of sentences silently omitted or re-ordered more logically than in this manuscript. Perhaps mockingly, Gauguin spells Huysmans with a W (either 'Wysmans' or 'Wuysmans') throughout.

The final article was published in the book "Gauguin, Oviri: Ecrits d'un sauvage", edited by Daniel Guérin (1974), pp. 59-61, dating it 'fin 1889', and noting that it was first published in Les Nouvelles littéraires, 7 May 1953. The manuscript shows significant differences from the published text, with a number of sentences silently omitted or re-ordered more logically than in this manuscript. Perhaps mockingly, Gauguin spells Huysmans with a W (either 'Wysmans' or 'Wuysmans') throughout.

1 available

Translated in part:

'The artist ... is one of [Nature's] means of creation'. A characteristically discursive, epigrammatic and trenchant comparison of the Decadent novelist and art critic Joris-Karl Huysmans and Odilon Redon, with comments on Gustave Moreau and Puvis de Chavannes. 'Wysmans [sic] is an artist [...] Many painters would like to be musicians or men of letters. He would like to be a painter [...]'; Gauguin felicitates Huysmans for his abandonment of naturalistic art, and continues with a critique of Huysmans's description of a Virgin and Child by Francesco Bianchi, in which he sees the writer projecting himself rather than truly interpreting the painting. He continues: "Bianchi, like all ancient painters, found around him in nature a mode in which he incorporated himself. I'd go further and say he made it in his image. Did God make man in his image or did man make God in his image? I am heavily in favour of the latter option. Consider the work of Rembrandt and Raphaël, and the intimate relation between their female and male models and their self-portraits. Many others as well. Bianchi didn't voluntarily put as much vicious malice into that painting described by Huysmans". On Redon, Gauguin remarks on his creation of 'monsters': 'I do not see how Odilon Redon creates monsters – they are imaginary beings. He is a dreamer, a man of imagination [...] If we carefuly examine the profound art of Redon, we find little trace of the monstrous, no more than the statues etc of Notre Dame [...] Nature has mysterious infinities, a power of imagination [...] The artist himself is one of her means of creation and for me Odilon Redon is one of her chosen ones for this continuation of creation [...] In all [Redon's] work I see only a language of the heart, quite human and not monstrous'. Gauguin contrasts with this Gustave Moreau, of whom Huysmans speaks highly: in him, Gauguin is far from seeing an impulsion of the heart: 'He makes of every human being a jewel covered in jewels. (The soul is missing)'. On Puvis de Chavannes, he comments that 'he does not smile at you [...] Simplicity, nobility are not suited to this age'. The manuscript ends with some disconnected notes, including one relating to his fascination with the South Pacific: 'Sea coconut – Coconut in two parts which open like the female genitalia, from which emerges an enormous phallus which embeds itself in the earth to germinate. The inhabitants have long considered it as the forbidden fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil'.

'The artist ... is one of [Nature's] means of creation'. A characteristically discursive, epigrammatic and trenchant comparison of the Decadent novelist and art critic Joris-Karl Huysmans and Odilon Redon, with comments on Gustave Moreau and Puvis de Chavannes. 'Wysmans [sic] is an artist [...] Many painters would like to be musicians or men of letters. He would like to be a painter [...]'; Gauguin felicitates Huysmans for his abandonment of naturalistic art, and continues with a critique of Huysmans's description of a Virgin and Child by Francesco Bianchi, in which he sees the writer projecting himself rather than truly interpreting the painting. He continues: "Bianchi, like all ancient painters, found around him in nature a mode in which he incorporated himself. I'd go further and say he made it in his image. Did God make man in his image or did man make God in his image? I am heavily in favour of the latter option. Consider the work of Rembrandt and Raphaël, and the intimate relation between their female and male models and their self-portraits. Many others as well. Bianchi didn't voluntarily put as much vicious malice into that painting described by Huysmans". On Redon, Gauguin remarks on his creation of 'monsters': 'I do not see how Odilon Redon creates monsters – they are imaginary beings. He is a dreamer, a man of imagination [...] If we carefuly examine the profound art of Redon, we find little trace of the monstrous, no more than the statues etc of Notre Dame [...] Nature has mysterious infinities, a power of imagination [...] The artist himself is one of her means of creation and for me Odilon Redon is one of her chosen ones for this continuation of creation [...] In all [Redon's] work I see only a language of the heart, quite human and not monstrous'. Gauguin contrasts with this Gustave Moreau, of whom Huysmans speaks highly: in him, Gauguin is far from seeing an impulsion of the heart: 'He makes of every human being a jewel covered in jewels. (The soul is missing)'. On Puvis de Chavannes, he comments that 'he does not smile at you [...] Simplicity, nobility are not suited to this age'. The manuscript ends with some disconnected notes, including one relating to his fascination with the South Pacific: 'Sea coconut – Coconut in two parts which open like the female genitalia, from which emerges an enormous phallus which embeds itself in the earth to germinate. The inhabitants have long considered it as the forbidden fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil'.